By Beatriz Astete Vilchez, Maryam Zolfaghari, Ana Grinfeld (Kaminskaya) and Jos de Boer

The method

In design, it’s common to first conduct some research before starting with the ideation, conceptualisation and even prototyping stage. Prototypes can really make a project come to live, and they can be used to gather valuable insights. It could be said, that testing prototypes is a form of research.

What happens if you turn the usual project structure around, and start by making prototypes? Letting users interact with prototypes can be a useful way to gather initial user data and feedback at the same time. By doing this in the first stages of a project, it is possible to rapidly make iterations, that speed up the design process. This method works especially well if you want to explore or experiment with different concepts, tech, and interactions. This method is related to rapid prototyping, although that method emphasizes bringing different concepts to life in a really short time span. Prototyping as Research focuses more on getting valuable data from tests with the prototypes.

Project Goals

We used this method during the second ‘Emerging Ecologies’ project at the Master Digital Design (schoolyear 2023-2024). Our brief was to make prototypes to let people experience the concept of an electrical grid. The electrical grid is the network that brings electricity from the source to electric outlets, and everything in between. Whilst making prototypes was our main deliverable for the project, we also decided that they could function as useful research tools. We wanted to experiment with different interactions, to find out what could engage people and let them ‘experience’ the electrical grid.

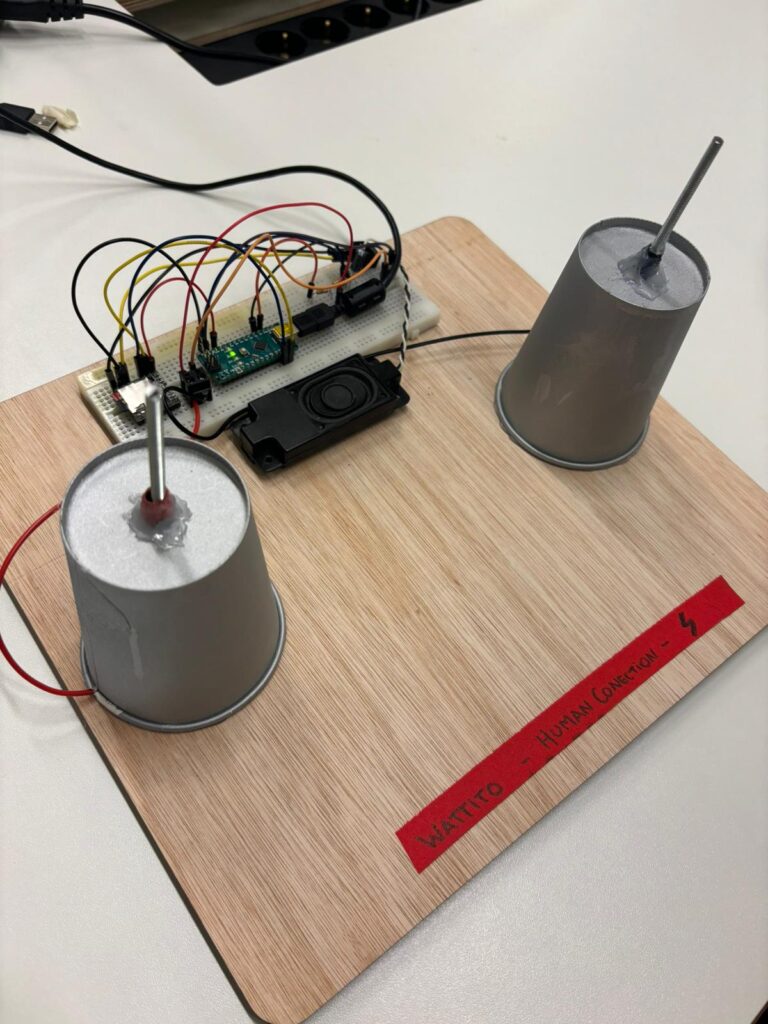

It was only logical that we’d use electronics in a project about electricity. Luckily, we have access to microcontrollers such as Arduino’s and a vast array of electronic components at the Master Digital Design. We started out by looking for some inspiration online. Luckily, tons of fun and interesting electronics can be found, with detailed instructions on how to replicate them. The main criteria for our search, was that the physical interaction had to be interesting and engaging. We came across a project, whereby two people enclose an electrical circuit by touching each other’s hand. Using an Arduino Nano, resistors a speaker and some slightly altered code, we were able to replicate this project in one day. It worked by touching two metal bars, that had a miniscule current running trough them (impossible to feel, I should add). By touching both bars, the circuit would be completed and a sound would play.

We wanted to see if people would find interacting with this contraption interesting. We didn’t have to wait long to get some answers. Other students were really curious, and started testing our device. We instructed them that it would still work when they formed a large circle, wherein everybody was touching or holding the hands of the people next to them. This prompted our classmates to form a large circle and test the machine. The main takeaway was that people don’t mind testing your work, as long as it is engaging – and fun!

We also made some other prototypes, such as an hourglass which would indicate how much energy had been used per a given time. This didn’t really work in the precise manner we were envisioning, but it was suitable enough to get the idea across to others (a key aspect of prototyping). Furthermore, we created an electronics prototype that addressed the fact that the power level on the grid constantly needs to be balanced. Both too little or too much energy on the grid can have catastrophic results. The first iteration of this prototype included a DC motor and a servo. Whilst powering a DC motor lets it spin, turning the shaft by hand will generate voltage. We converted the voltage being generated to movement of the servo. The servo was connected to a dial, that indicated a power level. The power level would slowly go down, and turning the handle connected to the motor would increase it again. The prototype was more or less a simple balance game.

When explaining and testing this prototype, it became clear to us that the concept needed some more work. The interaction of turning a handle and the concept of maintaining balance didn’t really match that well. We needed a new interaction that really emphasized the core concept. So, we made a wooden balance board with sensors that mapped the movement of the board unto the servo and dial. This second iteration really seemed to captivate people, as many of our classmates wanted to try it out.

Conclusion

The prototypes we made do not just function as testbeds for our end products, but they also shape the concept behind our project as well. At the time of writing, the project is still ongoing. Our team has just decided on a final overarching concept, that will tie the different prototypes together. In this regard, we departed from the traditional design process, as we first started prototyping before we had our concept fully laid out. Prototyping as Research can thus perhaps be seen as another way of doing initial research. Besides aiding with conceptualisation, testing the prototypes was also a way of doing user research. Additionally, it helped us with tweaking some coding issues early on.

To summarize: Prototyping as Research Is a useful and fun method that can help to generate ideas, do user testing and get feedback early-on in the design process.

Jos de Boer